Tree sort – binary search tree sort. Time complexity – O(n²). In such a tree, each node has numbers less than the node on the left, more than the node on the right, when coming from the root and printing the values from left to right, we get a sorted list of numbers. Surprising huh?

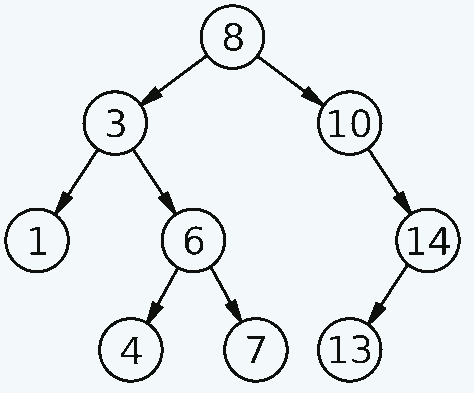

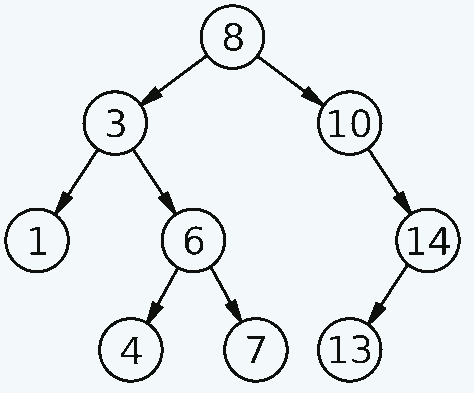

Consider the binary search tree schema:

Derrick Coetzee (public domain)

Try to manually read the numbers starting from the penultimate left node of the lower left corner, for each node on the left – a node – on the right.

It will turn out like this:

- The penultimate node at the bottom left is 3.

- She has a left branch – 1.

- Take this number (1)

- Next, take the vertex 3 (1, 3) itself

- To the right is branch 6, but it contains branches. Therefore, we read it in the same way.

- Left branch of node 6 number 4 (1, 3, 4)

- Node 6 itself (1, 3, 4, 6)

- Right 7 (1, 3, 4, 6, 7)

- Go up to the root node – 8 (1,3, 4 ,6, 7, 8)

- Print everything on the right by analogy

- Get the final list – 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 13, 14

To implement the algorithm in code, you need two functions:

- Building a binary search tree

- Printing the binary search tree in the correct order

They assemble a binary search tree in the same way as they read it, a number is attached to each node on the left or right, depending on whether it is less or more.

Lua example:

Node = {value = nil, lhs = nil, rhs = nil}

function Node:new(value, lhs, rhs)

output = {}

setmetatable(output, self)

self.__index = self

output.value = value

output.lhs = lhs

output.rhs = rhs

output.counter = 1

return output

end

function Node:Increment()

self.counter = self.counter + 1

end

function Node:Insert(value)

if self.lhs ~= nil and self.lhs.value > value then

self.lhs:Insert(value)

return

end

if self.rhs ~= nil and self.rhs.value < value then

self.rhs:Insert(value)

return

end

if self.value == value then

self:Increment()

return

elseif self.value > value then

if self.lhs == nil then

self.lhs = Node:new(value, nil, nil)

else

self.lhs:Insert(value)

end

return

else

if self.rhs == nil then

self.rhs = Node:new(value, nil, nil)

else

self.rhs:Insert(value)

end

return

end

end

function Node:InOrder(output)

if self.lhs ~= nil then

output = self.lhs:InOrder(output)

end

output = self:printSelf(output)

if self.rhs ~= nil then

output = self.rhs:InOrder(output)

end

return output

end

function Node:printSelf(output)

for i=0,self.counter-1 do

output = output .. tostring(self.value) .. " "

end

return output

end

function PrintArray(numbers)

output = ""

for i=0,#numbers do

output = output .. tostring(numbers[i]) .. " "

end

print(output)

end

function Treesort(numbers)

rootNode = Node:new(numbers[0], nil, nil)

for i=1,#numbers do

rootNode:Insert(numbers[i])

end

print(rootNode:InOrder(""))

end

numbersCount = 10

maxNumber = 9

numbers = {}

for i=0,numbersCount-1 do

numbers[i] = math.random(0, maxNumber)

end

PrintArray(numbers)

Treesort(numbers)

An important nuance is that for numbers that are equal to the vertex, a lot of interesting mechanisms for hooking to the node have been invented, but I just added a counter to the vertex class, when printing, the numbers are returned by the counter.

Links

https://gitlab.com/demensdeum /algorithms/-/tree/master/sortAlgorithms/treesort

References

TreeSort Algorithm Explained and Implemented with Examples in Java | Sorting Algorithms | Geekific – YouTube

Tree sort – YouTube

Convert Sorted Array to Binary Search Tree (LeetCode 108. Algorithm Explained) – YouTube

Sorting algorithms/Tree sort on a linked list – Rosetta Code

Tree Sort – GeeksforGeeks

Tree sort – Wikipedia

How to handle duplicates in Binary Search Tree? – GeeksforGeeks

Tree Sort | GeeksforGeeks – YouTube