In this note I will describe the basic principles of the well-known classic CRUD pattern, implementation in Swift. Swift is an open, cross-platform language available for Windows, Linux, macOS, iOS, Android.

There are many solutions for abstracting the data storage and application logic. One such solution is the CRUD approach, which is an acronym for C – Create, R -Read, U – Update, D – Delete.

Typically, this principle is implemented by implementing an interface to the database, in which elements are handled using a unique identifier, such as id. An interface is created for each CRUD letter – Create(object, id), Read(id), Update(object, id), Delete(object, id).

If the object contains an id inside itself, then the id argument can be omitted in some methods (Create, Update, Delete), since the entire object is passed there along with its – id field. But for – Read, an id is required, since we want to get the object from the database by identifier.

All names are fictitious

Let’s imagine that the hypothetical AssistantAI application was created using the free EtherRelm database SDK, the integration was simple, the API was very convenient, and the application was eventually released to the markets.

Suddenly, the SDK developer EtherRelm decides to make it paid, setting the price at $100 per year per user of the application.

What? Yes! What should the developers from AssistantAI do now, since they already have 1 million active users! Pay 100 million dollars?

Instead, a decision is made to evaluate the transfer of the application to the native RootData database for the platform; according to programmers, such a transfer will take about six months, without taking into account the implementation of new features in the application. After some thought, a decision is made to remove the application from the markets, rewrite it on another free cross-platform framework with a built-in BueMS database, this will solve the problem with the paid database + simplify development on other platforms.

A year later, the application was rewritten in BueMS, but then suddenly the framework developer decided to make it paid. It turns out that the team fell into the same trap twice, whether they will be able to get out the second time is a completely different story.

Abstraction to the rescue

These problems could have been avoided if developers had used interface abstraction within the application. To the three pillars of OOP – polymorphism, encapsulation, inheritance, not long ago another one was added – abstraction.

Data abstraction allows you to describe ideas and models in general terms, with a minimum of detail, while being precise enough to implement specific implementations that are used to solve business problems.

How can we abstract the work with the database so that the application logic does not depend on it? Let’s use the CRUD approach!

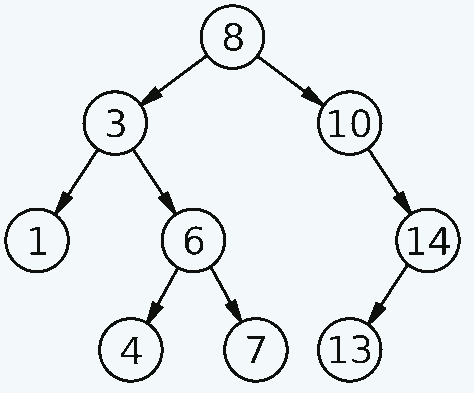

A simplified UML CRUD diagram looks like this:

Example with a fictitious EtherRelm database:

Example with a real SQLite database:

As you have already noticed, when switching a database, only it changes, the CRUD interface with which the application interacts remains unchanged. CRUD is a variant of the GoF pattern implementation – Adapter, since with its help we adapt the application interfaces to any database, combine incompatible interfaces.

Words are empty, show me the code

To implement abstractions in programming languages, interfaces/protocols/abstract classes are used. All of these are the same thing, but during interviews you may be asked to name the difference between them. Personally, I think that there is no particular point in this, since the only purpose of using them is to implement data abstraction, otherwise it is a test of the interviewee’s memory.

CRUD is often implemented within the Repository pattern, but a repository may or may not implement the CRUD interface, depending on the developer’s ingenuity.

Let’s look at a fairly typical Swift code for a Book structure repository that works directly with the UserDefaults database:

struct Book: Codable {

let title: String

let author: String

}

class BookRepository {

func save(book: Book) {

let record = try! JSONEncoder().encode(book)

UserDefaults.standard.set(record, forKey: book.title)

}

func get(bookWithTitle title: String) -> Book? {

guard let data = UserDefaults.standard.data(forKey: title) else { return nil }

let book = try! JSONDecoder().decode(Book.self, from: data)

return book

}

func delete(book: Book) {

UserDefaults.standard.removeObject(forKey: book.title)

}

}

let book = Book(title: "Fear and Loathing in COBOL", author: "Sir Edsger ZX Spectrum")

let repository = BookRepository()

repository.save(book: book)

print(repository.get(bookWithTitle: book.title)!)

repository.delete(book: book)

guard repository.get(bookWithTitle: book.title) == nil else {

print("Error: can't delete Book from repository!")

exit(1)

}

The code above seems simple, but let’s count the number of violations of the DRY (Do not Repeat Yourself) principle and the cohesion of the code:

Linked to UserDefaults database

Relationship with JSON encoders and decoders – JSONEncoder, JSONDecoder

Coherence with the Book structure, and we need an abstract repository so as not to create a repository class for each structure that we will store in the database (violation of DRY)

I come across such CRUD repository code quite often, it can be used, however, high cohesion, code duplication, lead to the fact that over time its support will become very complicated. This will be especially noticeable when trying to switch to another database, or when changing the internal logic of working with the database in all repositories created in the application.

Instead of duplicating code, keeping high coupling – let’s write a protocol for a CRUD repository, thus abstracting the database interface and the application’s business logic, observing DRY, implementing low coupling:

typealias Item = Codable

typealias ItemIdentifier = String

func create<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws

func read<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws -> T

func update<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws

func delete(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws

}

The CRUDRepository protocol describes interfaces and associated data types for further implementation of a specific CRUD repository.

Next, we will write a specific implementation for the UserDefaults database:

private typealias RecordIdentifier = String

let tableName: String

let dataTransformer: DataTransformer

init(

tableName: String = "",

dataTransformer: DataTransformer = JSONDataTransformer()

) {

self.tableName = tableName

self.dataTransformer = dataTransformer

}

private func key(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) -> RecordIdentifier {

"database_\(tableName)_item_\(id)"

}

private func isExists(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws -> Bool {

UserDefaults.standard.data(forKey: key(id: id)) != nil

}

func create<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws {

let data = try await dataTransformer.encode(item)

UserDefaults.standard.set(data, forKey: key(id: id))

UserDefaults.standard.synchronize()

}

func read<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws -> T {

guard let data = UserDefaults.standard.data(forKey: key(id: id)) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

let item: T = try await dataTransformer.decode(data: data)

return item

}

func update<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws {

guard try await isExists(id: id) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

let data = try await dataTransformer.encode(item)

UserDefaults.standard.set(data, forKey: key(id: id))

UserDefaults.standard.synchronize()

}

func delete(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws {

guard try await isExists(id: id) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

UserDefaults.standard.removeObject(forKey: key(id: id))

UserDefaults.standard.synchronize()

}

}

The code looks long, but it contains a complete concrete implementation of a CRUD repository with loose coupling, details below.

typealias are added to make the code self-documenting.

Weak coupling and strong coupling

Decoupling from a specific structure (struct) is implemented using the generic T, which in turn must implement the Codable protocols. Codable allows you to convert structures using classes that implement the TopLevelEncoder and TopLevelDecoder protocols, such as JSONEncoder and JSONDecoder, when using basic types (Int, String, Float, etc.) there is no need to write additional code to convert structures.

Decoupling from a specific encoder and decoder is done using abstraction in the DataTransformer protocol:

func encode<T: Encodable>(_ object: T) async throws -> Data

func decode<T: Decodable>(data: Data) async throws -> T

}

With the implementation of the data transformer, we implemented an abstraction of the encoder and decoder interfaces, implementing loose coupling to ensure work with different types of data formats.

The following is the code for a specific DataTransformer, namely for JSON:

func encode<T>(_ object: T) async throws -> Data where T : Encodable {

let data = try JSONEncoder().encode(object)

return data

}

func decode<T>(data: Data) async throws -> T where T : Decodable {

let item: T = try JSONDecoder().decode(T.self, from: data)

return item

}

}

Was it possible?

What has changed? Now it is enough to initialize a specific repository to work with any structure that implements the Codable protocol, thus eliminating the need for code duplication, and implementing weak application coupling.

An example of client CRUD with a specific repository, UserDefaults acts as a database, the data format is JSON, the structure is Client, also an example of writing and reading an array:

print("One item access example")

do {

let clientRecordIdentifier = "client"

let clientOne = Client(name: "Chill Client")

let repository = UserDefaultsRepository(

tableName: "Clients Database",

dataTransformer: JSONDataTransformer()

)

try await repository.create(id: clientRecordIdentifier, item: clientOne)

var clientRecord: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print("Client Name: \(clientRecord.name)")

clientRecord.name = "Busy Client"

try await repository.update(id: clientRecordIdentifier, item: clientRecord)

let updatedClient: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print("Updated Client Name: \(updatedClient.name)")

try await repository.delete(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

let removedClientRecord: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print(removedClientRecord)

}

catch {

print(error.localizedDescription)

}

print("Array access example")

let clientArrayRecordIdentifier = "clientArray"

let clientOne = Client(name: "Chill Client")

let repository = UserDefaultsRepository(

tableName: "Clients Database",

dataTransformer: JSONDataTransformer()

)

let array = [clientOne]

try await repository.create(id: clientArrayRecordIdentifier, item: array)

let savedArray: [Client] = try await repository.read(id: clientArrayRecordIdentifier)

print(savedArray.first!)

During the first CRUD check, exception handling has been implemented, in which case reading of the remote item will no longer be available.

Switching databases

Now I will show how to transfer the current code to another database. For example, I will take the code of the SQLite repository that ChatGPT generated:

class SQLiteRepository: CRUDRepository {

private typealias RecordIdentifier = String

let tableName: String

let dataTransformer: DataTransformer

private var db: OpaquePointer?

init(

tableName: String,

dataTransformer: DataTransformer = JSONDataTransformer()

) {

self.tableName = tableName

self.dataTransformer = dataTransformer

self.db = openDatabase()

createTableIfNeeded()

}

private func openDatabase() -> OpaquePointer? {

var db: OpaquePointer? = nil

let fileURL = try! FileManager.default

.url(for: .documentDirectory, in: .userDomainMask, appropriateFor: nil, create: false)

.appendingPathComponent("\(tableName).sqlite")

if sqlite3_open(fileURL.path, &db) != SQLITE_OK {

print("error opening database")

return nil

}

return db

}

private func createTableIfNeeded() {

let createTableString = """

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS \(tableName) (

id TEXT PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL,

data BLOB NOT NULL

);

"""

var createTableStatement: OpaquePointer? = nil

if sqlite3_prepare_v2(db, createTableString, -1, &createTableStatement, nil) == SQLITE_OK {

if sqlite3_step(createTableStatement) == SQLITE_DONE {

print("\(tableName) table created.")

} else {

print("\(tableName) table could not be created.")

}

} else {

print("CREATE TABLE statement could not be prepared.")

}

sqlite3_finalize(createTableStatement)

}

private func isExists(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws -> Bool {

let queryStatementString = "SELECT data FROM \(tableName) WHERE id = ?;"

var queryStatement: OpaquePointer? = nil

if sqlite3_prepare_v2(db, queryStatementString, -1, &queryStatement, nil) == SQLITE_OK {

sqlite3_bind_text(queryStatement, 1, id, -1, nil)

if sqlite3_step(queryStatement) == SQLITE_ROW {

sqlite3_finalize(queryStatement)

return true

} else {

sqlite3_finalize(queryStatement)

return false

}

} else {

print("SELECT statement could not be prepared.")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

}

func create<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws {

let insertStatementString = "INSERT INTO \(tableName) (id, data) VALUES (?, ?);"

var insertStatement: OpaquePointer? = nil

if sqlite3_prepare_v2(db, insertStatementString, -1, &insertStatement, nil) == SQLITE_OK {

let data = try await dataTransformer.encode(item)

sqlite3_bind_text(insertStatement, 1, id, -1, nil)

sqlite3_bind_blob(insertStatement, 2, (data as NSData).bytes, Int32(data.count), nil)

if sqlite3_step(insertStatement) == SQLITE_DONE {

print("Successfully inserted row.")

} else {

print("Could not insert row.")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

} else {

print("INSERT statement could not be prepared.")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

sqlite3_finalize(insertStatement)

}

func read<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws -> T {

let queryStatementString = "SELECT data FROM \(tableName) WHERE id = ?;"

var queryStatement: OpaquePointer? = nil

var item: T?

if sqlite3_prepare_v2(db, queryStatementString, -1, &queryStatement, nil) == SQLITE_OK {

sqlite3_bind_text(queryStatement, 1, id, -1, nil)

if sqlite3_step(queryStatement) == SQLITE_ROW {

let queryResultCol1 = sqlite3_column_blob(queryStatement, 0)

let queryResultCol1Length = sqlite3_column_bytes(queryStatement, 0)

let data = Data(bytes: queryResultCol1, count: Int(queryResultCol1Length))

item = try await dataTransformer.decode(data: data)

} else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

} else {

print("SELECT statement could not be prepared")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

sqlite3_finalize(queryStatement)

return item!

}

func update<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws {

guard try await isExists(id: id) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

let updateStatementString = "UPDATE \(tableName) SET data = ? WHERE id = ?;"

var updateStatement: OpaquePointer? = nil

if sqlite3_prepare_v2(db, updateStatementString, -1, &updateStatement, nil) == SQLITE_OK {

let data = try await dataTransformer.encode(item)

sqlite3_bind_blob(updateStatement, 1, (data as NSData).bytes, Int32(data.count), nil)

sqlite3_bind_text(updateStatement, 2, id, -1, nil)

if sqlite3_step(updateStatement) == SQLITE_DONE {

print("Successfully updated row.")

} else {

print("Could not update row.")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

} else {

print("UPDATE statement could not be prepared.")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

sqlite3_finalize(updateStatement)

}

func delete(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws {

guard try await isExists(id: id) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

let deleteStatementString = "DELETE FROM \(tableName) WHERE id = ?;"

var deleteStatement: OpaquePointer? = nil

if sqlite3_prepare_v2(db, deleteStatementString, -1, &deleteStatement, nil) == SQLITE_OK {

sqlite3_bind_text(deleteStatement, 1, id, -1, nil)

if sqlite3_step(deleteStatement) == SQLITE_DONE {

print("Successfully deleted row.")

} else {

print("Could not delete row.")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

} else {

print("DELETE statement could not be prepared.")

throw CRUDRepositoryError.databaseError

}

sqlite3_finalize(deleteStatement)

}

}

Or the CRUD repository code for the file system, which was also generated by ChatGPT:

class FileSystemRepository: CRUDRepository {

private typealias RecordIdentifier = String

let directoryName: String

let dataTransformer: DataTransformer

private let fileManager = FileManager.default

private var directoryURL: URL

init(

directoryName: String = "Database",

dataTransformer: DataTransformer = JSONDataTransformer()

) {

self.directoryName = directoryName

self.dataTransformer = dataTransformer

let paths = fileManager.urls(for: .documentDirectory, in: .userDomainMask)

directoryURL = paths.first!.appendingPathComponent(directoryName)

if !fileManager.fileExists(atPath: directoryURL.path) {

try? fileManager.createDirectory(at: directoryURL, withIntermediateDirectories: true, attributes: nil)

}

}

private func fileURL(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) -> URL {

return directoryURL.appendingPathComponent("item_\(id).json")

}

private func isExists(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws -> Bool {

return fileManager.fileExists(atPath: fileURL(id: id).path)

}

func create<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws {

let data = try await dataTransformer.encode(item)

let url = fileURL(id: id)

try data.write(to: url)

}

func read<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws -> T {

let url = fileURL(id: id)

guard let data = fileManager.contents(atPath: url.path) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

let item: T = try await dataTransformer.decode(data: data)

return item

}

func update<T: CRUDRepository.Item>(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier, item: T) async throws {

guard try await isExists(id: id) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

let data = try await dataTransformer.encode(item)

let url = fileURL(id: id)

try data.write(to: url)

}

func delete(id: CRUDRepository.ItemIdentifier) async throws {

guard try await isExists(id: id) else {

throw CRUDRepositoryError.recordNotFound(id: id)

}

let url = fileURL(id: id)

try fileManager.removeItem(at: url)

}

}

Replacing the repository in the client code:

print("One item access example")

do {

let clientRecordIdentifier = "client"

let clientOne = Client(name: "Chill Client")

let repository = FileSystemRepository(

directoryName: "Clients Database",

dataTransformer: JSONDataTransformer()

)

try await repository.create(id: clientRecordIdentifier, item: clientOne)

var clientRecord: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print("Client Name: \(clientRecord.name)")

clientRecord.name = "Busy Client"

try await repository.update(id: clientRecordIdentifier, item: clientRecord)

let updatedClient: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print("Updated Client Name: \(updatedClient.name)")

try await repository.delete(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

let removedClientRecord: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print(removedClientRecord)

}

catch {

print(error.localizedDescription)

}

print("Array access example")

let clientArrayRecordIdentifier = "clientArray"

let clientOne = Client(name: "Chill Client")

let repository = FileSystemRepository(

directoryName: "Clients Database",

dataTransformer: JSONDataTransformer()

)

let array = [clientOne]

try await repository.create(id: clientArrayRecordIdentifier, item: array)

let savedArray: [Client] = try await repository.read(id: clientArrayRecordIdentifier)

print(savedArray.first!)

Initialization of UserDefaultsRepository has been replaced with FileSystemRepository, with appropriate arguments.

After running the second version of the client code, you will find a directory “Clients Database” in the documents folder, which will contain a file of a serialized array in JSON with one Client structure.

Switching the data storage format

Now let’s ask ChatGPT to generate an encoder and decoder for XML:

let formatExtension = "xml"

func encode<T: Encodable>(_ item: T) async throws -> Data {

let encoder = PropertyListEncoder()

encoder.outputFormat = .xml

return try encoder.encode(item)

}

func decode<T: Decodable>(data: Data) async throws -> T {

let decoder = PropertyListDecoder()

return try decoder.decode(T.self, from: data)

}

}

Thanks to Swift’s built-in types, the task becomes elementary for a neural network.

Replace JSON with XML in the client code:

print("One item access example")

do {

let clientRecordIdentifier = "client"

let clientOne = Client(name: "Chill Client")

let repository = FileSystemRepository(

directoryName: "Clients Database",

dataTransformer: XMLDataTransformer()

)

try await repository.create(id: clientRecordIdentifier, item: clientOne)

var clientRecord: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print("Client Name: \(clientRecord.name)")

clientRecord.name = "Busy Client"

try await repository.update(id: clientRecordIdentifier, item: clientRecord)

let updatedClient: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print("Updated Client Name: \(updatedClient.name)")

try await repository.delete(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

let removedClientRecord: Client = try await repository.read(id: clientRecordIdentifier)

print(removedClientRecord)

}

catch {

print(error.localizedDescription)

}

print("Array access example")

let clientArrayRecordIdentifier = "clientArray"

let clientOne = Client(name: "Chill Client")

let repository = FileSystemRepository(

directoryName: "Clients Database",

dataTransformer: XMLDataTransformer()

)

let array = [clientOne]

try await repository.create(id: clientArrayRecordIdentifier, item: array)

let savedArray: [Client] = try await repository.read(id: clientArrayRecordIdentifier)

print(savedArray.first!)

The client code has changed only by one expression JSONDataTransformer -> XMLDataTransformer

Result

CRUD repositories are one of the design patterns that can be used to implement weak coupling of application architecture components. Another solution is to use ORM (Object-relational mapping), in short, ORM uses an approach in which structures are completely mapped to the database, and then changes with models should be displayed (mapped (!)) to the database.

But that’s a completely different story.

A complete implementation of CRUD repositories for Swift is available at:

https://gitlab.com/demensdeum/crud-example

By the way, Swift has long been supported outside of macOS, the code from the article was completely written and tested on Arch Linux.

Sources

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/combine/topleveldecoder

https://developer.apple.com/documentation/combine/toplevelencoder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Create,_read,_update_and_delete